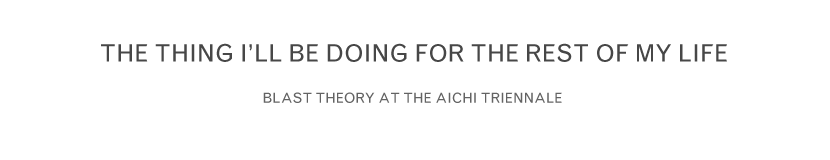

Today I arrived in Nagoya and went straight from the airport to Toyohama Port, with Yasunori – who will assist me and translate everything for the project that I need and Noriko one of the assistant curators who will make sure everything that I need to happen does happen.

We went to see Eight Prosper Circle, our boat.

This is Takeshi Ishiguro, Noriko and Yasunori pulling the rope so I can jump on board first.

And here’s me on board – ridiculously happy and jetlagged.

Ishiguro means “black stone” and is co-ordinating every aspect of moving the boat, including a big barbeque on Sunday for all the volunteers and the Triennale team. Ishiguro is now more worried about the food as he’s a big party host and loves to karaoke.

Everyone is coming down to watch, the officials who granted the permissions for the boat to travel along the road, the owner of the lorry company and the director of the Triennale. I am hoping that I can persuade them to get involved.

The vessel was made 40 years ago by the Yamaha Corporation in Nagoya and has been given to our project by Minoru Amano, the lovely man below.

It has no engine, the top of the cabin will need to be taken off to get it under road bridges and it is generally in very bad shape. He will build the cradle or support structure for the exhibition and his daughter-in-law lived in the UK for a couple of years.

I asked him about what he thought would be the perfect end to this boat and he said:

“ He wasn’t sure how to answer this. She might get broken into pieces and recycled into oil. But you can’t have lots of retired boats just sitting there in the port as there would be no room for new boats.”

In this port and town they have an incredible festival every year at the end of July to celebrate or give thanks to the sea bream. It started 140 years ago and here is a video to give you some idea.

http://www.e-tanakaya.com/?page_id=15

Everyone in the district has to contribute to the construction in some way and here are this years’ fish under way. The festival once used animals from the Japanese horoscope, no one seems to know why it changed to fish.

We will just miss these new fish coming out of the sea onto land by a few days, the festival is on 27th July with fireworks too and I leave on the 23rd July. This year the local people will see this old ship coming out of the water one last time. The people I have met seem curious about this.

Tomorrow we must clean all the shells and seaweed off the bottom of the hull because the smell is apparently so bad that no one would be able to pull it out the way it smells now. I’m looking forward to this.

Oh one last thing, I ate fish today, the last time I ate fish was in Japan 10 years ago.

Share

Share